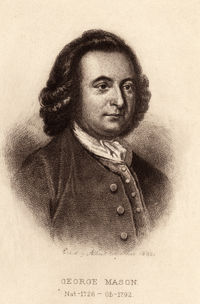

George Mason

| George Mason IV | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | George Mason December 11, 1725 Fairfax County, Colony of Virginia |

| Died | October 7, 1792 (aged 66) Gunston Hall, Fairfax County, Virginia |

| Cause of death | natural causes |

| Residence | Gunston Hall, Fairfax County, Virginia |

| Nationality | British, American |

| Ethnicity | English American |

| Citizenship | Kingdom of Great Britain United States |

| Occupation | patriot, statesman, and delegate from Virginia to the U.S. Constitutional Convention |

| Religion | Anglican, Episcopalian |

| Spouse | Ann Eilbeck Sarah Brent |

| Children | George Mason V Ann Eilbeck Mason Johnson William Mason William Mason Thomson Mason Sarah Eilbeck Mason McCarty Mary Thomson Mason Cooke John Mason Elizabeth Mason Thornton Thomas Mason James Mason Richard Mason |

| Parents | George Mason III Ann Stevens Thomson |

George Mason IV (December 11, 1725 – October 7, 1792) was an American patriot, statesman, and delegate from Virginia to the U.S. Constitutional Convention. Along with James Madison, he is called the "Father of the Bill of Rights."[1][2][3][4] For these reasons he is considered one of the "Founding Fathers" of the United States.[5][6]

Like anti-federalist Patrick Henry, Mason was a leader of those who pressed for the addition of explicit States rights [7] and individual rights to the U.S. Constitution as a balance to the increased federal powers, and did not sign the document in part because it lacked such a statement. His efforts eventually succeeded in convincing the Federalists to add the first ten amendments of the Constitution. These amendments, collectively known as the Bill of Rights, were based on the earlier Virginia Declaration of Rights, which Mason had drafted in 1776.

On the nagging issue of slavery, Mason walked a fine line. Although a slaveholder himself, he found slavery repugnant for a variety of reasons. He wanted to ban further importation of slaves from Africa and prevent slavery from spreading to more states. However, he did not want the new federal government to be able to ban slavery where it already existed, because he anticipated that such an act would be difficult and controversial.

Contents |

Family

George Mason was born on December 11, 1725 to George and Ann Thomson Mason at the Mason family plantation in Fairfax County, Virginia. His father died in 1735 in a boating accident on the Potomac, when the boat capsized and he drowned. After this event the younger Mason lived with his uncle John Mercer. On April 4, 1750, he married sixteen-year-old Ann Eilbeck, from a plantation in Charles County, Maryland.[8] They lived in a house on his property in Dogue's Neck, Virginia. Mason completed construction of Gunston Hall, a plantation house on the Potomac River, in 1759. He and his wife had twelve children, nine of whom survived to adulthood. Mason's first child, George Mason V of Lexington[9], was born on April 30, 1753. He married Elizabeth Mary Ann Barnes Hooe (Betsy) on April 22, 1784, and after having six children, died on December 5, 1796. The next Mason offspring was Ann Eilbeck Mason, fondly known as Nancy. Born on January 13, 1755, she married Rinaldo Johnson on February 4, 1789 and had three children before dying in 1814. The third child was named William Mason, but he did not live over a year and died in 1757. The fourth child, born on October 22, 1757, was also named William Mason, and he married Ann Stuart on July 11, 1793. They had five children together, and he died in 1818. The fifth child was a son they named Thomson Mason. He was born on March 4, 1759 and died on March 11, 1820. Thomson married Sarah McCarty Chichester of Newington in 1784; they had eight children.

George Mason's sixth child, christened Sarah Eilbeck Mason but fondly known as Sally, was born on December 11, 1760 and married in 1778. She had ten children with her husband Daniel McCarty, Jr. before dying on September 11, 1823. The seventh of the Mason children was another girl, Mary Thomson Mason. She was born on January 24, 1764, and married John Travers Cooke on November 18, 1784, with whom she had ten children before dying in 1806. John Mason was Mason's eighth child, being born on April 4, 1766. He married Anna Marie Murray on February 14, 1796, had ten children, and died on March 19, 1849. The ninth child was a daughter named Elizabeth Mason. She was born on April 19, 1768 and died sometime between 1792 and June of 1797. She married William Thornton in 1789 and they had two children. The tenth child, Thomas Mason, was born on May 1, 1770 and died on September 18, 1800. He married Sarah Barnes Hooe on April 22, 1793 and the two had four children together.

George Mason's last two children were James and Richard Mason; twins who were born in December, 1772 but died six weeks later. Their mother died three months later on March 9, 1773 due to complications. George Mason remarried on April 11, 1780 but did not have any children with his new wife, Sarah Brent. George Mason also suffered from the condition known as gout for a large part of his life, and in accordance with current medical treatment, relied upon bloodletting.

Mason had virtually no formal schooling and essentially educated himself from his uncle's library.[10]

Politics

Mason served at the Virginia Convention in Williamsburg in 1776. During this time he created drafts of the first declaration of rights and state constitution in the Colonies. Both were adopted after committee alterations; the Virginia Declaration of Rights was adopted June 12, 1776, and the Virginia Constitution was adopted June 29, 1776.

Mason was appointed in 1786 to represent Virginia as a delegate to a Federal Convention, to meet in Philadelphia for the purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation. He served at the Federal Convention in Philadelphia from May to September 1787 and contributed significantly to the formation of the Constitution. "He refused to sign the Constitution, however, and returned to his native state as an outspoken opponent in the ratification contest." [11] One objection to the proposed Constitution was that it lacked a "declaration of rights". As a delegate to Virginia's ratification convention, he opposed ratification without amendment. Among the amendments he desired was a bill of rights. This opposition, both before and during the convention, may have cost Mason his long friendship with his neighbor George Washington, and is probably a leading reason why George Mason became less well-known than other U.S. founding fathers in later years. On December 15, 1791, the U.S. Bill of Rights, based primarily on George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights, was ratified in response to the agitation of Mason and others.

At the convention, Mason was one of the five most frequent speakers. Mason believed in the disestablishment of the church. Mason was a strong anti-federalist who wanted a weak central government, divided into three parts, with little power, leaving the several States with a preponderance of political power. [12]

An important issue for him in the convention was the Bill of Rights. He did not want the United States to be like England. He foresaw sectional strife and feared the power of government. [13]

Slavery

A Virginia planter, Mason owned many black slaves. Like some of his contemporary slave owners (e.g. Thomas Jefferson and George Washington), Mason conceded that the institution was morally objectionable, once calling it a "slow Poison" that "is daily contaminating the Minds & Morals of our People." [14] Mason favored the abolition of the slave trade, but he did not advocate for the immediate abolition of slavery. Like Jefferson, he owned slaves whom he did not set free.

Two of Mason's stated reasons for opposing the U.S. Constitution were seemingly contradictory: on the one hand, he said that the draft Constitution did not specifically protect the right of states to let slavery continue where it already existed, and on the other hand he also said that the draft Constitution did not allow Congress to immediately stop the importation of slaves.[14][15] Mason's immediate concern was to prevent more slaves from being imported, and to prevent slavery from spreading into more states.[16] He was not eager to ban slavery where it already existed: "It is far from being a desirable property. But it will involve us in great difficulties and infelicity to be now deprived of them."[16] Mason ostensibly balanced his anti-slavery argument that importation should stop, with a pro-slavery argument that the draft Constitution should protect slavery from being taxed out of existence; however, the latter argument had already been incorporated into the Constitution according to James Madison.[17]

Because of his efforts to stop the spread of slavery, and his recognition of the undesirability of slavery, some historians have said that Mason should be categorized as an abolitionist.[18] Other historians have disagreed.[18]

Death and remembrance

George Mason died peacefully at his home, Gunston Hall, on October 7, 1792. Gunston Hall, located in Mason Neck, Virginia, is now a museum and tourist attraction. The George Mason Memorial in West Potomac Park, Washington, D.C., near the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, was dedicated on April 9, 2002. The George Mason Memorial Bridge connects Washington, DC, to Virginia. George Mason Elementary School in Alexandria, Virginia, George Mason High School in Falls Church, Virginia and George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia, are named in his honor, as are Mason County, Kentucky, Mason County, West Virginia and Mason County, Illinois. He was honored by the United States Postal Service with an 18¢ Great Americans series postage stamp.

References

- ↑ "The New United States of America Adopted the Bill of Rights: December 15, 1791". The Library of Congress. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/cgi-bin/page.cgi/jb/nation/bofright_1. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Heymsfeld, Carla R.; Lewis, Joan W. (1991). George Mason, father of the Bill of Rights. Alexandria, Va.: Patriotic Education Inc.. ISBN 0912530162. http://catalog.loc.gov/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?v3=1&DB=local&CMD=010a+91067692+&CNT=10+records+per+page

- ↑ Spratt, Tammy. "Father" of Our Country vs. "Father" of the Bill of Rights". The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. http://www.historynow.org/09_2007/lp4.html. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ "Bill of Rights Day - December 15th". Bill of Rights Defense Committee. http://www.bordc.org/resources/borhistory.php. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Yardley, Jonathan (November 5, 2006). A founding father insisted that the Constitution wasn't worth ratifying without a bill of rights. The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/02/AR2006110201182_pf.html. Retrieved 2007-12-06

- ↑ Henderson, Denise; Henderson, Frederic W. (March 15, 1993). How The Founding Fathers Fought For An End To Slavery. The American Almanac. http://american_almanac.tripod.com/ffslave.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-06

- ↑ Gutzman, Kevin (2007). The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution. Washington: Regnery Publishing, Inc.. pp. 35,23.

- ↑ Rowland, Kate Mason (1892). The Life of George Mason, 1725-1792. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 56. http://books.google.com/?id=F0F6TuWe_LwC&pg=PA56&lpg=PA56&dq=%22george+mason%22+%22charles+county%22. Retrieved 2007-12-13

- ↑ "Hollin Hall". George Mason's Plantations and Landholdings. Gunston Hall Plantation official website. http://look.net/gunstonhall/landholdings/. Retrieved 2007-02-29.

- ↑ From Revolution to Reconstruction: Biographies: George Mason II

- ↑ Borden, Morton, ed. (1965). The Anti federalist Papers. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. pp. ix.

- ↑ Gutzman, Kevin (2007). The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Constitution. Washington: Regnery Publishing, Inc.. pp. 35,23.

- ↑ Broadwater, Jeff (2006-09-01). George Mason: Forgotten Founder. Chapel Hill: Fred W. Morrison Fund for Southern Studies of the University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3053-6.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "George Mason's Views on Slavery"

- ↑ This issue is further discussed in Joseph J. Ellis, Founding Brothers (Knopf, 2000).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 See Kaminski, John. Necessary Evil?: Slavery and the Debate Over the Constitution, pages 59 and 186 (Rowman & Littlefield 1995). Mason said: "The Western people are already calling out for slaves for their new lands; and will fill that country with slaves, if they can be got through South Carolina and Georgia....[T]he General Government should have the power to prevent the increase of slavery."

- ↑ See "Debate in Virginia Ratifying Convention", The Founders’ Constitution (transcript from 1788-06-15). Mason said, "There is no clause in this Constitution to secure it; for they may lay such a tax as will amount to manumission." Madison responded: "From the mode of representation and taxation, Congress cannot lay such a tax on slaves as will amount to manumission....The census in the Constitution was intended to introduce equality in the burdens to be laid on the community."

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 See Broadwater, Jeff. George Mason, Forgotten Founder page 294, note 39 (UNC Press 2006).

Bibliography

- Bailyn, Bernard, ed. (1993). The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle over Ratification, 2 vols. Library of America.

- Broadwater, Jeff (2006-09-01). George Mason: Forgotten Founder. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Fred W. Morrison Fund for Southern Studies of the University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3053-6.

- Curtis, Barbara Jocelyn (1938). George Mason, Statesman, Rebel, Public Servant.

- Hawkes, Robert T., Jr. (1996). "An Uncommon American Hero: George Mason And The Bill Of Rights". Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Magazine 1 (46): 5328–5338.

- Henriques, Peter R. (1989). "An Uneven Friendship: The Relationship Between George Washington And George Mason". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 2 (97): 185–204.

- Jensen, Merrill et al., eds. (1976-). The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution of the United States, 20 vols. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

- Ketcham, Ralph, ed. (1986). The Anti-Federalist Papers and the Constitutional Convention Debates. Penguin.

- Lee, Emery G. (1997). "Representation, Virtue, and Political Jealousy in the Brutus-Publius Dialogue". The Journal of Politics (Cambridge University Press) 59 (4): 1073–1095. doi:10.2307/2998593. http://jstor.org/stable/2998593.

- Leffler, Richard (1987). "The Case Of George Mason's Objections To The Constitution". Manuscripts 4 (39): 285–292.

- Meltzer, Milton (1990). The Bill Of Rights: How We Got It And What It Means. New York: Thomas Crowell.

- Miller, Helen Hill (July 2001) [1938]. George Mason, Constitutionalist. Safety Harbor, Fl.: Simon Publications. ISBN 1931313458.

- Miller, Helen Hill (1966) [1938]. George Mason, Constitutionalist. Gloucester: P. Smith.

- Pole, J.R., ed. (1987). The American Constitution--For And Against: The Federalist And Anti-Federalist Papers. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Rowland, Kate Mason (1892). The Life Of George Mason, 1725-1792. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. http://books.google.com/?id=F0F6TuWe_LwC&dq=dogue's+neck.

- Rutland, Robert A. (September 1980). George Mason : Reluctant Statesman.

- Rutland, Robert A., et al. eds. (1970). The papers of George Mason, 3 vols. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Storing, Herbert, ed. (1985). The Anti-Federalist. University of Chicago Press.

- Storing, Herbert; Murray Dry, eds. (1981). The Complete Anti-Federalist 7 vol. University of Chicago Press.

External links

- George Mason biography

- Gunston Hall Home Page

- Amazing Mason by John J. Miller

- Website of George Mason University

- George Mason University Study Abroad- Center for Global Education

- MasonStudents - GMU's Student Run Discussion Forum

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||